Sample Speaking and Writing responses are a useful element of CELPIP preparation and a versatile classroom resource. This post will discuss where to find them, how to choose them, and what you can do with them.

Where to Find Sample Responses

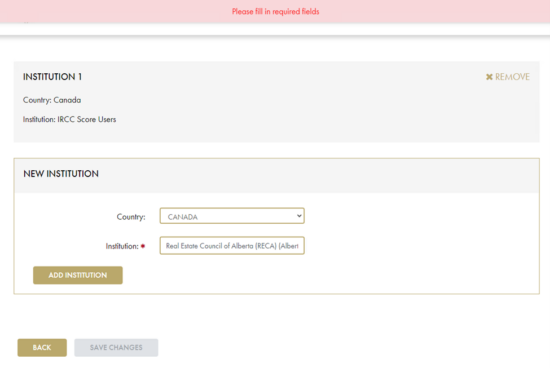

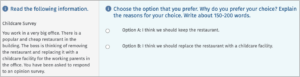

Free rated sample responses are included in the CELPIP Score Comparison Chart, which can be found here. For both Speaking and Writing, the Score Comparison Chart includes two real test taker responses at each CELPIP level. Speaking responses include both audio clips and transcripts. Each pair of responses comes with detailed analysis of how the test taker demonstrated the skills required for achieving that level. The two prompts for each pair of responses are the same, which facilitates comparison of responses at different levels.

Another source of sample responses is the study packs that accompany the free CELPIP Speaking Pro and Writing Pro webinars. These study packs include all the sample responses covered in the session, and can be found here (Speaking) and here (Writing). The sample responses for the Target 5 sessions are at or around a level 5, while those for the Target 9+ sessions are at or around a level 9. All responses include levels and analysis.

Lastly, instructors are strongly encouraged to work through the free Level 1 and Level 2 CELPIP Instructor Training courses, both of which include rated sample responses at a variety of levels, along with detailed analysis. The Level 2 training also includes two sets of three rated Writing responses that can be downloaded and used for classroom activities. Monthly registration dates are available for both levels; you can learn more here.

Choosing Sample Responses

Test takers benefit most from working with responses at or below their own level. For example, if most of the class is at a high intermediate level (say, around CLB or CELPIP level 7), they’ll learn the most from studying responses around level 5-7. This way, they’ll be able to identify strengths and weaknesses, compare the approaches of different test takers, correct errors, and suggest improvements, and they’ll likely gain awareness of their own strengths and weaknesses and get ideas about how to approach their own responses in the process.

Despite the above, test takers are especially eager to see or hear high-level responses; webinar attendees, for example, often ask if they’ll get to hear or see a level 12. Although it’s fine to share some of these to satisfy learners’ curiosity, they’re not a useful foundation for classroom activities unless the learners are at an advanced language level themselves.

When choosing responses, keep in mind that with the exception of those included in the instructor training courses, the sample responses discussed and linked above are available to everyone, including test takers. This means that if there are learners in your course who have attended CELPIP webinars or looked through the Score Comparison Chart, they may have encountered some or all of these responses before. However, this doesn’t mean you can’t use them in class. A learner can be aware of what level a response received or have a general idea of its content and still benefit from a new activity that uses it.

Regardless of which responses you choose, the first step is to familiarize yourself with them so that you’ll be able to lead productive discussions of their strengths and weaknesses, choose activities that suit their content and language level, and be ready to explain any grammar or vocabulary questions learners may have.

Working with Sample Responses

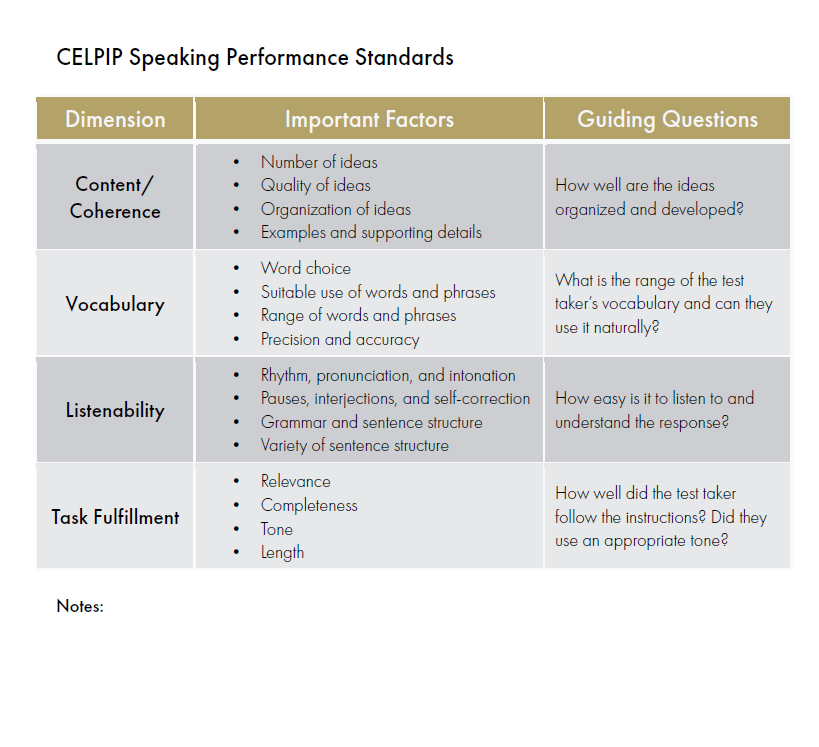

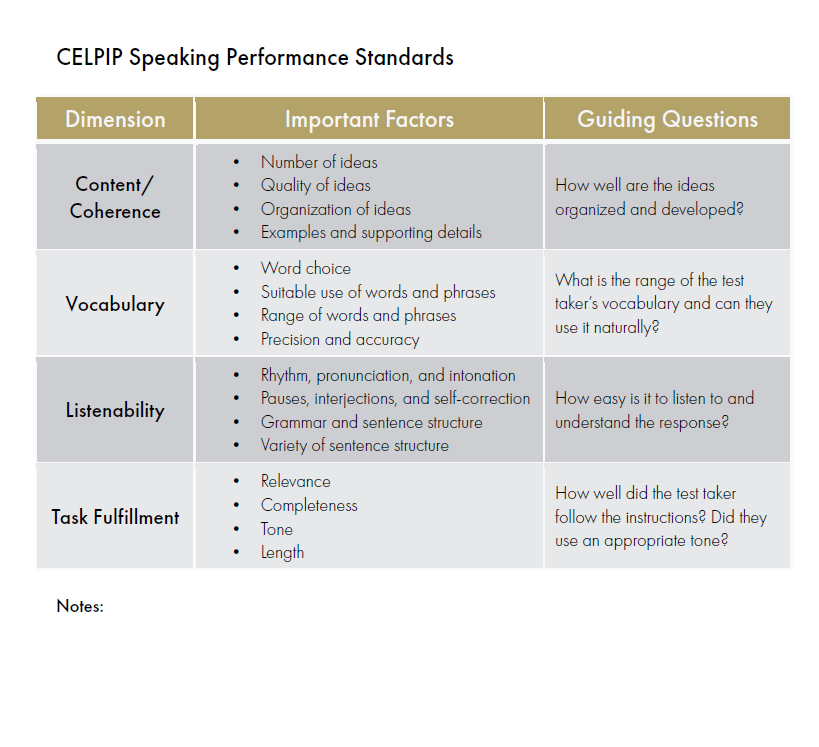

With sample responses, the more specific and active the task is, the better. Learners gain language skills not by simply reading or listening to others’ responses, but by analyzing, comparing, and improving them. The Performance Standards, a simplified version of what raters use to assess Speaking and Writing responses, can be used for all of these purposes. They are included as a PDF download accompanying this post, and instructors are strongly encouraged to use them in class for analysis of test taker responses as well as peer editing tasks and productive skills feedback.

In the case of Speaking responses, providing a transcript (or having learners create one) is often advisable, as it allows learners to work with the response more efficiently. While transcripts are never created or used by raters, they are often a helpful tool in a classroom context.

Comparing Responses at Different Levels

The Score Comparison Chart, mentioned above, is a valuable resource for learners and teachers alike. As its name suggests, it’s an ideal way for learners to compare responses rated at different levels. Choosing two responses at different levels (say, 7 and 9) and having learners compare them is the best way to give concrete answers to common test taker questions like “What’s the difference between a level 7 and a level 9?” While it is possible for CELPIP test takers to have different strengths and weaknesses and still earn the same level in Writing or Speaking, the responses in the Score Comparison Chart have been chosen as strong representatives of that level in each dimension. As a result, actively identifying their strengths and weaknesses and learning how those translate to an overall level will provide insight into scoring and, more importantly, help learners realize which skills they should work on to achieve the best possible test results.

Working with the Level Descriptors

As the Score Comparison chart also includes the skills required for each level—called the Level Descriptors—another useful activity is to ask learners to decide whether a particular response meets all of the criteria for a certain level—or, if their language level is strong, to have them compare a response to the criteria on the chart and see if they can determine roughly which level the response received. This is a way to have learners identify specific skills that a learner has demonstrated, as well as weaknesses that may have prevented them from achieving a higher level. This activity works best with learners at the intermediate stage and higher, as understanding the Level Descriptors well enough to apply them to sample responses requires a solid grasp of English.

Identifying Strengths (and Weaknesses)

When presented with a sample response, test takers have a tendency to notice weaknesses more readily than strengths, and many are especially fixated on pointing out grammatical errors. There are several ways to help learners develop a bigger-picture and more even-handed perspective of all the factors present in a productive skills response and how they impact its quality. One is to instruct them to focus on strengths. Have them look at each factor of each dimension of the Performance Standards and determine what the test taker is doing well, highlighting specific examples of those strengths. Let the class know that raters do this too: they don’t scan for problems or count errors; they consider each factor and identify specific examples to support their assessments. Depending on the response, it may also be useful to discuss which dimension they consider to be the strongest overall, and why.

Even when discussing weaknesses, you can set up parameters to direct test takers to consider factors other than grammar. For example, you can divide them into groups and have each group consider a different dimension of the Performance Standards, or a specific factor within a dimension, such as organization, amount of supporting detail, range of vocabulary, or relevance.

Error Correction

For an error correction task, it’s best to choose a response that contains some errors that your learners will have the ability to identify and fix, but not so many that the content can’t be understood or the response needs to be completely recreated. A variety of approaches can be taken to error correction. For example, you could group or pair up learners and instruct each group to find and correct a certain number of errors (say, 5). Then, as a class, have each group report on the errors they found, discuss how to correct them, and finally identify and correct any remaining errors as a class. Another approach is to divide the response into sections and assign one to each group to correct. Or, you can identify the errors yourself and give learners the task of explaining why each one is a mistake and suggesting a correction.

Making Improvements

Improving a response is a beneficial next step to identifying weaknesses. This is another exercise in which learners will likely focus on grammar problems unless directed otherwise. There are many aspects besides grammar that benefit from active consideration: for example, organization, level of detail, word choice, use of transitions, staying on topic, and fully addressing each part of the task. As with error correction, it’s best to choose a response with a reasonable number of opportunities for improvement that your learners will have the ability to notice. For beginner or low-intermediate learners, making improvements at a sentence level might be most appropriate. Higher-level learners can work in pairs or groups to improve multiple elements and rewrite, or even re-record, an entire response.

Vocabulary Cloze

Printing and adding some blanks to a high-level response can be a way to teach some new vocabulary in context. Choose a response that includes some useful language you think will be new to your learners, make a list of the words, and then blank them out in the response. As you fill in the blanks, discuss the meaning and pronunciation of each word and how it might be used in other sentences. Using a high-level response works best for this activity so that learners don’t become distracted by errors. You might even want to retype the response with the errors corrected.

Approaches to Avoid

As a final note, there are a couple of approaches that should not be taken in prep courses. First, it’s extremely important not to require learners to memorize “model” or “perfect” sample responses. In some countries, this is a commonly assigned task, and instructors may also suggest that learners imitate such responses in their own speaking and writing or use them as templates. However, this should not be encouraged by CELPIP prep instructors anywhere in the world, because memorizing, copying, and templating are the opposite of what is required of CELPIP test takers. Every test taker signs a contract stating that they will produce spontaneous and original responses. Those who include memorized or copied content in their tests are subject to invalidation of their test results, as explained in a short video here.

Another activity to avoid is “guess the level”: playing or displaying a response and having test takers announce which CELPIP level they think it received. Learners, understandably, tend to be rather obsessed with levels, and guessing is harmless fun—but it shouldn’t be the endpoint of a learning exercise. Rating is a complex process in which two or three extensively trained, highly fluent English users assess multiple dimensions of each response according to a detailed rubric. As nobody in the classroom, instructor included, is a CELPIP rater, this process can’t be imitated there. Of course, it’s absolutely fine to tell learners what level a response received; doing so after discussing its strengths and weaknesses is usually the best strategy. This way learners can associate the level with specific skills that the test taker demonstrated or didn’t.